The Drama of Artist Payments

In recent times, artists/songwriters, who once made their living recording and writing songs, have been severely affected by the slump in royalty revenue coming from labels, publishers, and rights organizations. The decline is not only attributed to piracy and market trends, but to a shift in consumer demand to digital delivery formats. Artists/ songwriters claim the new music economy is not compensating them fairly or evenly, and this paper draws together recent research on the subject.

Context

A growing number of artists and songwriters have come forward to voice their dissatisfaction with the little money they receive from digital streaming. Some artists who are fortunate to control their own recordings have gone as far as to pull out their catalogs from streaming services like Spotify, YouTube, and Apple Music1 while others strike lucrative deals to make their catalogs available to streaming sites for the first time.2 Songwriters who are not also recording artists with some level of control over their recordings aren’t as lucky. The combination of traditional record label deals signed early in their careers, the section 115 compulsory licenses, and the ASCAP and BMI antitrust laws have made it impossible for them to take any action against these services. But digital streaming also includes YouTube, which is regarded as the largest music streaming site in the world and is largely governed by private dealings and not the rules that audio-only internet radio services like Pandora are subject to. YouTube in particular is notorious for its measly and erratic payouts3 and under the protection of the DMCA Safe Harbors (section 512 of the Copyright Act) it is probably the largest provider of music copyright infringing material on the web.4 The thousands of sites where songs are streamed, the different types of digital streaming services that exist, and the different laws/ regulations/ ratesetting models that apply in each case have combined to create a chaotic environment where the parties that stand to lose are the service providers/platforms/organizations that license music as part of their business and the talented artists, producers, and songwriters that create it.

The Shift in Consumer Demand

There has been a dramatic shift in the way music is consumed in the last fifteen years— from CD purchases, to downloads, to digital streaming which has gone from representing barely 3% of the US recorded music revenues in 2007 to 34% in 20155, ten times more! The shift from brick-and-mortar distribution to digital retail, and now to streaming, translates to lower mechanical royalties for publishers and songwriters who in the past benefited from the sale of complete albums (traditionally an album cut would produce as much mechanical revenue as the most popular single in the album). The Nashville Songwriters Association (NSAI) reports mechanical royalty6 declines “in the order of 60-70% or more.” Songwriters who happen not to be performing artists are especially hard hit because they can’t make up for the loss by touring or selling merchandise. NSAI reports the number of fulltime songwriters falling by 80% since the year 2000.7 A well known contributor to The New Yorker reports, “If streaming is the future of music, songwriters may soon be back to where they started: broke!”8

The Music Rights In Question

In the realm of digital streaming services, song and sound recording copyright owners are entitled to collect on three major rights:

1. The right to reproduce.

2. The right to distribute. Together with the right to reproduce, this is the “mechanical” right.

3. The right to perform publicly.

As mentioned earlier, a form of digital streaming that adds a visual component to a copyrighted work, as is the case with sites like YouTube or Vevo, adds a fourth right, the right to create a derivative work. Known as “synchronization” or “synch” rights, these are generally understood to be a combination of the owners’ reproduction and derivative work rights.9

Because laws/ regulations are typically created for technology and industry practices that exist at the time that they are enacted, changes and advances in technology over time have resulted in legal patchwork and consequently anomalies in the market for sound recordings. A few examples:

– Rights at the federal level apply only to recordings made after February 15, 1972. The decision made by Congress in 1971 to leave pre-1972 recordings under common state laws has gone from “a copyright oddity to a serious legal issue”10 with several lawsuits and resulting settlements taking place in 2015. 11

– Terrestrial (broadcast) radio stations are exempt from paying for any sound recording public performance rights. This 1972 law was passed when artists and labels relied on AM/ FM radio broadcasters to promote their music, which, broadcasters argued, turned into increased profits for record labels and artists from album sales and touring. In today’s satellite radio and digital streaming market, such promotional value is arguably a fraction of what it used to be.

Streaming Revenue and Distribution

For Spotify, the largest digital streaming service in the world, negotiations to plan its launch in the US were so complex that it took years before an agreement was reached. Founder Daniel Ek said of his experience, “If anyone had told me going into this that it would be three years of crashing my head against the wall, I wouldn’t have done it.”12

Part of the complexity involves new legislation that makes a clear distinction between:

– Services that play music randomly (although these services may allow the user to influence what they want to listen to by stating a preferred genre or favorite artist) Example: Pandora and SiriusXM. And,

– Services that allow users to stream music on-demand, meaning that users can specify exactly what song or album they would like to listen to. Example: Spotify and Tidal.

The first type of digital streaming service is known as “internet radio” or “non-interactive” while the second is known as “on-demand” or “interactive.”

A third distinction is made on:

– Services that include video. Example: YouTube and Vevo.

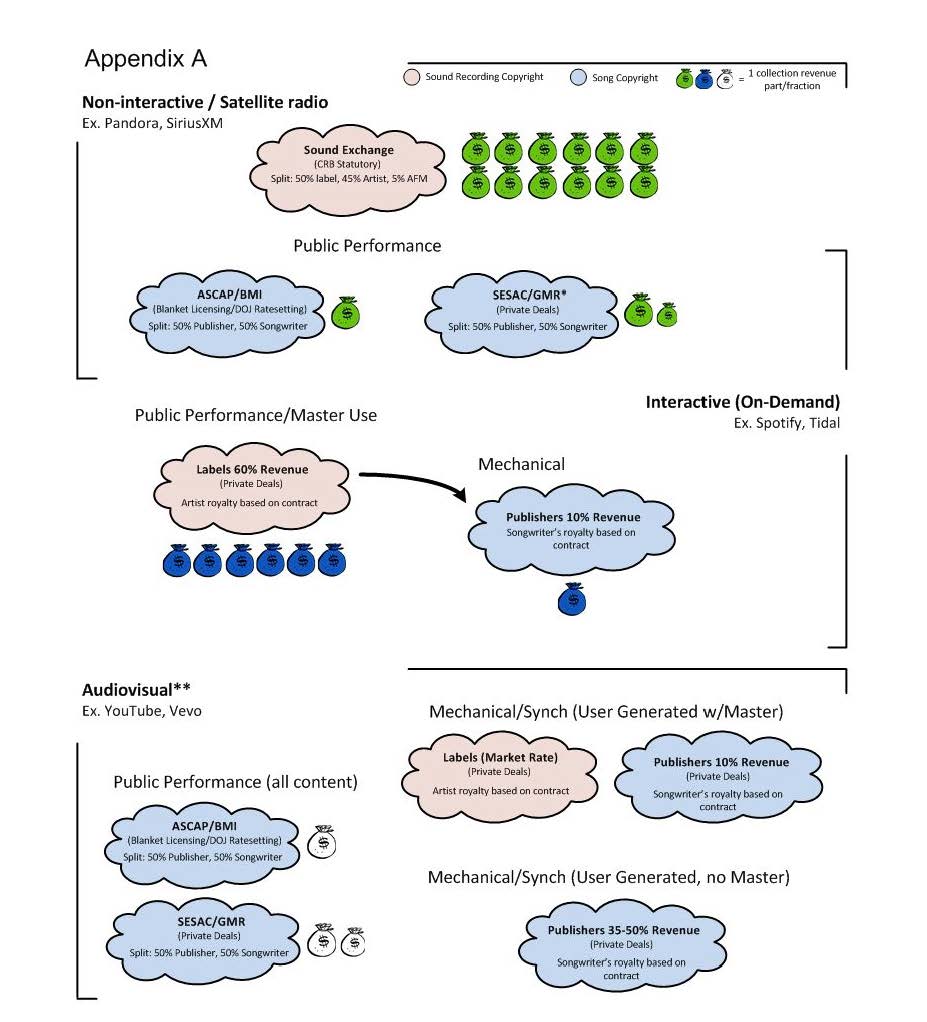

Appendix A shows the streaming models, what source of income is collected by performance rights organizations (PROs), record labels, and publishers. Where known, the revenue split is shown.

Sound Exchange (SoX) is an independent nonprofit organization that collects statutory license-only, non-interactive sound recording public performance royalties on behalf of label and artist members. A digital radio performance of a popular song recording may generate revenue for both SoX as well as ASCAP/BMI who collect on behalf of publisher and songwriter members. However, as Appendix A shows, SoX’s collections for the same stream as compared to those of ASCAP/BMI are much higher, reportedly by a ratio of 12:1 (some say as high as 14:1).13 Bette Midler’s highly publicized $114.11 royalty payment from Pandora for 4 million plus plays can in fact be shown to yield a high ratio of 23:1.

It is worth noting that SoX does not collect royalties for digital services that include an audiovisual component (e.g. YouTube, Vevo). YouTube, the world’s biggest music streaming service, enters into direct, private deals with copyright owners for mechanical/synchronization rights.

However, the DMCA Harbors protects sites like YouTube for any content “posted on their systems at the direction of users,”14 in essence, passing over to copyright owners the responsibility for notifying YouTube about the infringement, which they do by means of takedown notices. The DMCA Safe Harbors law has been highly controversial as it sets the stage for a continuous flow of copyright infringing material and takedown notices which in 2014 alone averaged 345 million or 940,000 per day!15 Copyright owners insist that it should be Google’s responsibility to obtain a license for each use while Google is happy to adhere to the DMCA Safe Harbors which basically state the onus is upon rightsholders to tell it what specifically to remove. In other words, shall the use of copyrighted works online be “opt-in or opt-out?”16 Google argues in favor of the benefits of the DMCA Safe Harbors which promote user online content-sharing services and points to the “immense collateral damage that would occur to all UGC (user generated content)-sharing services if storage safe harbors were restricted.”17

Services like YouTube are free to the user and Spotify offers a free tier to entice users into a paid service. It is reported that the ratio of free to paid users in Spotify is 3 to 118. Free, ad-supported services contribute to dilute the income generated by labels and publishers as these kind of streams pay less than subscriber streams because Spotify and Google make less on ads than on subscriptions. Surprisingly, label revenue generated by ad-supported streaming services like Spotify has been recently surpassed by revenue generated from the sale of vinyl records!19

The presence of a free tier was the reason licensing content to Spotify took so long because when Spotify started, the free tier was an on-demand service and record labels opposed it arguing, rightly so, that it would cannibalize the downloads market and perhaps what was left of the physical product market. Spotify argues that since it has to pay a large share of its revenues as royalties, it has little to no room for a marketing budget and the free tier is an effective form of marketing for the premium version. Spotify accounts that it converts about a quarter of its non-paying users into premium subscribers. When asked about Apple’s music service who does not offer a permanent free tier, Spotify’s answer is simple: “We don’t have a phone business.”20

As far as the value of each stream, the average is approximately 6/10 to 8/10 of a cent.21 That means that a $1.29 song download is equivalent to about 160 to 215 streams. To calculate the royalty rate per stream, Spotify divides up the monthly streams of an artist’s song by the total number of streams in that month. That tiny share is multiplied by the total monthly revenues minus 30%. However, as mentioned before, some streams are worth less than others based on geographical location and whether the stream is from a free service.

Spotify’s website states that its premium service “delivers more than two times the amount of revenue to the industry (per year) as the average US music consumer currently does,”22 citing an NPD Group statistic which states that out of an internet population of 190 million, only 45% consume music and those who do spend $55/year compared to the $120/year they would spend for a Spotify full subscription. While the numbers appear realistic, the premise in that argument is not because $55/year is taking into account a market where piracy and free services like the Pirate Bay and YouTube and even Spotify’s own free tier dominate.

Because record labels typically require licensees to sign non-disclosure agreements, the exact terms of their private dealings with Spotify were unknown. That is until late 2014 when a highly publicized hacking scandal leaked a copy of Sony Music’s licensing agreement with Spotify. The document confirmed that record labels receive approximately 60 to 70% of subscriptions and ad revenue yet only 14 to 16% of what they receive or 10% of the overall Spotify revenue is paid to publishers.

Presumably, a relevant factor in this determination is the royalty rate established by the CRB (Copyright Royalty Board) for mechanical licensing of physical records and downloads which many claim “does not reflect the fair market value of musical works and acts as a ceiling that does not allow publishers to seek higher royalties through voluntary negotiations.23

The fact that mechanical licensing is compulsory makes matters worse for publishers as they are bound to accept a low rate currently set at 9.1 cents for most songs. Said rate “has not kept pace with the times, since the original 2 cent rate set by statute in 1909 represents 51 cents today when adjusted for inflation.”24

The advent of interactive digital streaming was perhaps an opportunity to offset the low mechanical license rates of physical sales and downloads and provide publishers with a higher royalty pool. In the corporate boardrooms of the large music corporations, however, record label interests appear to have taken precedence. One music publisher described the scenario as it appears to have happened, “Basically, the major music corporations sold out their publishing companies in order to save their record labels which in the end, means that the songwriter got screwed.”25

It is well known too that the share of artist and publishing royalties has not varied by much despite the elimination of certain costs such as packaging/manufacturing and distribution. Whereas the two are not necessarily connected, many in the industry argue that the record labels’ keeping of a larger share of the revenue from today’s digital stream in comparison to what they kept from yesterday’s CD appears unjustified.

Conflict Over NDAs

It is no secret that labels received a stake in Spotify, collectively owning about 15% of the company. The question of major record labels owning equity in a major player in the digital streaming service market has raised concerns of fair competition among Spotify’s rivals and independent artists. As of July 2015, before Apple launched it’s on-demand digital streaming service, Spotify accounted for 86% of the market in the US.26 If Apple, Amazon, or Google— who have a steady profit from a multitude of sources— try to undercut Spotify’s prices to hinder its dominance, how would the labels respond? An insider label source was quoted as saying, “You might want to take a discount in a business you have equity in, you might not want to take a discount in a business you don’t have equity in.”27

If we consider the overall income generated by digital service providers, a number of intriguing questions come to mind: How are the financial benefits of advances and advertising space to record labels shared with artists and songwriters? What about capital gains derived from the equity they own, is that benefit shared with artists/songwriters? What about those artists that have old recording contracts without any payout provisions for digital streaming?

Sony’s deal with Spotify revealed the presence of big royalty advances in the order of $9 to $17.5 million per year in quarterly installments which aren’t treated as royalty revenue until Spotify actually reports on period stream data. Advances are of course recoupable, but include a “minimum guaranteed revenue clause,”28 which essentially means that if either the advance or the agreed minimum guaranteed exceed the royalties/revenue sharing earned during the licensing period, then the label is protected thanks to “breakage” and gets to keep the difference.

After the hacking scandal, Warner Music Group was the first major record label to clarify convincingly its policy of sharing all advance monies (including “breakage”) with artists and to state that it has been honoring that policy since 2009. Warner Music artist royalty statements made public in 2015 confirm the claim.29 While Sony Music and Universal followed suit with similar public statements, both failed to provide a time since the policy has been in place and most importantly whether or not they share all or only a portion of the unallocated income from advances.30

Other clauses in the same deal “allow Spotify to keep 15% of its ad revenues sold by third parties ‘off the top’ without accounting them as revenue” and also require Spotify to give Sony “advertising inventory at a discounted rate in the amount of $2.5 to $3.5 million per year, which Sony is then able to resell for a profit.”31 It is unclear how these obscure arrangements provide any benefit to artists and publishers/songwriters.

Reportedly, Spotify’s dealings with indie labels or digital distributors such as Tunecore are much more transparent than those with the majors, with timely payments accompanied by monthly statements and streaming details neatly broken down per artist.32

PRO Consent Decrees and Rate-Setting

The Department of Justice (DOJ) consent decrees were signed by ASCAP and BMI in 1941 in response to antitrust complaints and radio boycotts which attempted to curb the dominant position and resulting abu- sive practices that ASCAP had established in the marketplace. The consent decrees laid out a set of rules governing the operation of the two PROs.33

Among them:

– PROs can’t refuse to grant a license to any user that applies even if pricing terms are not agreed to by licensees.

– Licensing terms should be the same and cannot discriminate against licensees in similar standing/positions.

– PROs must offer alternatives to the blanket licensees if requested.

– PROs may only represent nonexclusive rights.

The decrees basically shifted the balance of power away from the PROs and to songwriter/publisher members and licensees. With the shift in consumer demand, away from terrestrial radio/TV and into the digital/online space, the existence of the consent decrees gave digital service providers such as Pandora and iHeart Radio an enormous advantage heading into rate negotiations.

Since licensees are able to start performing ASCAP/BMI repertoire as soon as they apply for a license without having to agree on a rate, they can choose to rely on interim fees while long ratesetting processes take place or they can delay payments and potentially leave creators without compensation for an extended period of time.34

The NMPA blames the ratesetting procedures established by the consent decrees (currently two judges in New York District Courts with antitrust concerns) as the source of the exceptionally low rates paid for the public performance of a composition,35 which “deflate royalties below their true market value.”36

Adding to the imbalance is the disparity in the law created by Congress’ decision to not require broadcast TV/radio stations to obtain licenses for public performance rights of sound recordings. This terrestrial radio exemption also limits sound recording copyright owners’ ability to collect royalties on foreign radio/TV broadcasts as most foreign collection agencies would not release the funds due to lack of reciprocity.37 It’s possible that the revenue lost due to this exemption influenced how market forces interacted to even the playing field in favor of record labels and artists when it came time to set rates for digital radio service providers like Pandora and SiriusXM.

It is worth noting that the DOJ consent decrees only apply to ASCAP and BMI repertoire, but not to Global Music Rights (GMR), a newcomer PRO that started operations in 2013, and SESAC repertoire, both of whom represent significant catalogs of works. This disparity of application gives a competitive advantage to newer PROs that are not subject to the same anti-trust regulations. GMR was founded around the time the issue of “fractional licensing” came about— when publishers attempted a partial withdrawal of ‘new media’ or digital rights from ASCAP/BMI. The goal of the publishers was to circumvent the norms set by the DOJ consent decrees so they could negotiate directly with digital service providers at higher rates.

Just as publishers started to have success negotiating private deals with digital service providers like Pandora that would have increased songwriting revenue from public performances in the digital space, the DOJ rate courts ruled that “partial withdrawal of rights was not permitted,” forcing music publishers to back out.38

Conclusion

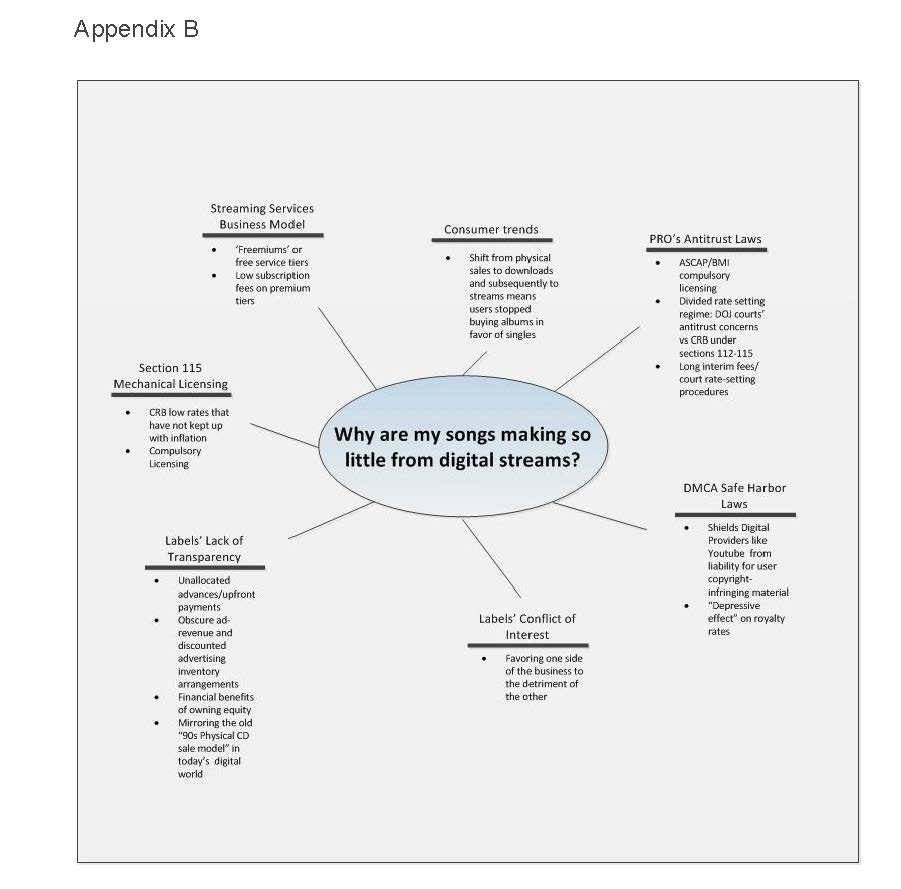

Appendix B summarizes the issues contributing to the decline in artist and songwriting royalty income. The issues appear to fall into one of three categories: regulatory, business/organizational, and market-oriented. Some of the issues/categories are interconnected, and therefore influence or impact one another. For example: regulations such as the DMCA Safe Harbors that are well-intentioned but not free of collateral damage to intellectual property rights.

While online piracy and shifting consumer patterns are a contributing factor, it is fair to hold that the lack of an integral solution that addresses the diverse licensing needs of music users in the marketplace in addition to the lack of fair, flexible, and comprehensive government regulations bear the greatest impact on the measly royalty checks artists, but particularly songwriters, receive today.

The aggravation of artists and songwriters with traditional record labels and publishers comes across in their readiness to join newer “label services”, “rights management”, and “collection services” organizations which provide more flexibility, transparency and control. Companies such as BMG Rights and Kobalt perhaps represent the hottest growth sector in the music industry offering artists and songwriters something “simple and fair, rather than a takeover of rights, a partnership opportunity where clients construct their own budgets and decide their own future.”39

For music publishers, the absurd disproportion of royalty payments collected for song copyrights vs. sound recording copyrights is driving a transformation that puts ASCAP/BMI at risk of losing major catalogue representations. But performance rights is not the only source of income where an inequity exists. In the area of mechanical rights, publishers ask, for example, why is it that revenue from privately negotiated, “free market” synchronization licenses generally reflect a 1-to-1 ratio between musical works and sound re- cordings but the sale of CDs, downloads, and interactive streams generate mechanical revenue that on average reflects a 1-to-7 ratio.40

The hacked licensing agreement between Sony and Spotify shined a light on the various payment arrangements between the two organizations and to no one’s surprise, it was the record label siphoning off most of the revenue and diverting only a small portion back to the artists they represent and claim to care about.41 Moreover, the major music companies’ conservative stance and reluctance to adapt and transform in light of a new business model era appears baffling. The lack of transparency demonstrated only upholds the belief that conflicts of interest in the music industry exist and the party who has the upper hand will always put their interests ahead regardless.42

Service providers like Spotify readily defend their models, basically stating that “a little money is better than free.” For artists, per- haps the stage at which their careers are plays a part. Developing artists and established artists with solid catalogues that tour extensively need the exposure and can probably take the loss. However, artists that do not tour as much or are growing their catalogues cannot afford it.

Several in this latter group have expressed that they prefer to continue to weather the storm than settle for pocket change. With the pocket change also comes the impact of a continued degradation in the perceived value of music. The fact that the revenue generated by the sale of such a niche product as vinyl records has been able to generate more revenue than free/ad-supported digital streaming ($226 million vs. $162.7 million in the first half of 2015) is perhaps the best indicator of the music industry’s “poor ability to monetize its non-physical products.”43 Both the RIAA and Spotify appear to agree that while paid services continue to compete with “free,” market forces will not let digital streaming subscription service rates go any higher.

By Harold Coleridge

Endnotes:

1.‘Islands in the Stream: The 10 Biggest Holdouts in Digital Music’, Steve Knopper (January, 2015)

2.‘Digital music antagonists Metallica finally come to Spotify’, Bryan Bishop (December, 2012); Pink Floyd Catalog Arrives on Spotify (June, 2013)

3.‘Revenue Streams’, John Seabrook (November, 2014)

4.Copyright and the Music Marketplace [Report], Page 80

5.Recording Industry Reports Revenue Increase Due to Streaming, WSJ (March, 2016)

6.Copyright and the Music Marketplace [Report], Page 72

7.Copyright and the Music Marketplace [Report], Page 78

8.‘Will Streaming Music Kill Songwriting’, John Seabrook (February, 2016)

9.Buffalo Broad. v. ASCAP, 744 F.2d at 920; Agee, 59 F.3d at 321

10.‘What’s the Deal With Pre1972 Sound Recordings?’, Plagiarism Today (August, 2013)

11.‘Pandora Reaches $90 Million Settlement With Labels Over Pre1972 Music’, Gardner (October, 2015)

12.Revenue Streams’, John Seabrook (November, 2014)

13.Money For Something: Music Licensing in the 21st Century, p.24 (Dana A. Sherer)

14.Legal Protection of Digital Information, http://digital-law-online.info/lpdi1.0/treatise33.html

15.Copyright and the Music Marketplace [Report], Page 80

16.Pharrell Williams’ Lawyer to YouTube: Remove Our Songs or Face $1 Billion Lawsuit, Hollywood Reporter (December, 2014)

17.Targeting Safe Harbors To Solve The Music Industry’s YouTube Problem, A Bridy (April, 2015)

18.“All you Need to Know About the Music Business” (D. Passman, 2015)

19.Vinyl Record Revenues Have Surpassed Free Streaming Services Like Spotify, E.Mann (October, 2015)

20.Why does Spotify cling to its free music tier? , Bloomberg (December, 2015)

21.http://www.spotifyartists.com/spotifyexplained/

22.http://www.spotifyartists.com/spotifyexplained/

23.Copyright and the Marketplace Report, Page 105

24.Copyright and the Marketplace Report, Page 106

25.Revenue Streams’, John Seabrook (November, 2014)

26.Apple, Feeling Heat From Spotify, to Offer Streaming Music Service, Smith/Wakabayashi (June, 2015)

27.Revenue Streams’, John Seabrook (November, 2014)

28.Sony: We Share Spotify Advances With Our Artists”, Tim Hingham (May, 2015)

29.Warner Pays Artists Share of Spotify Advances… and Has for 6 years, Tim Ingham (May, 2015)

30.Sony: We Share Spotify Advances With Our Artists / Universal: Yes We Share Digital Breakage Money With Our Artists, Tim Ingham (May/June, 2015)

31.Spotify, Sony Deal Shows Where the Revenue Flows and How Pinched the Streaming Services Are, Joel Hruska (May, 2015) 32.Revenue Streams’, John Seabrook (November, 2014)

33.‘Conflict over Consent Decrees’, BCM Music Business Journal (Griffin Davis)

34.Copyright and the Music Marketplace [Report], Page 94

35.‘Conflict over Consent Decrees’, BCM Music Business Journal (Griffin Davis)

36.Copyright and the Music Marketplace [Report], Page 92

37.‘RIAA First Notice Comments’, P.3031

38.Global Music Rights, ASCAP, BMI, and Pandora Get Nitty and Gritty in CMJ Discussion, A. Flanagan (Octo- ber, 2015)

39.Forget a Record Deal, Get a Rights Management Deal, M. St James (April, 2013)

40.Copyright and the Marketplace, Page 106

41.‘Spotify, Sony deal shows where the revenue flows and how pinched the streaming services are’, J.Hruska (May, 2015)

42.Rethink Music, BCM, Fair Music: Transparency and Payment Flows in the Music Industry (July, 2015)

43.Vinyl Record Revenues Have Surpassed Free Streaming Services Like Spotify, E.Mann (October, 2015)

Informative.

Good job!