Using Kickstarter To Raise Money

Lately, it seems that phrases like “direct-to-fan” and “fan funding” have been echoing off the walls. In the last few years, artists like Trent Reznor and Radiohead have pioneered a new kind of marketing using the Internet’s vast power of communication to make more personal connections with their fans. In many cases, this has yielded some overwhelmingly positive results –Reznor scored an in-pocket $750,000 in just a few days selling a limited-edition box set to fans in 2008.

However, at this point, most independent artists would complain that the luxury of these types of revenues is only available to those that have a pre-established fan base. On the other hand, authors Craig Mod and Ashley Rawlings, would beg to differ. In funding their latest book, Art Space Tokyo, the duo meticulously researched kickstarter.com’s greatest success stories and formulated a plan that generated an impressive $24,000 in just 30 days. Their findings provide some very enlightening information that could apply to creators in all mediums.

Musicians and Variable Pricing

Kickstarter is the definition of fan funding. Independent musicians, writers, entrepreneurs, etc. can use the service to present their idea to a world wide web of potential investors. The site allows anyone who feels so inclined to contribute money to a given project by selecting one of the many price tiers available –ranging from $1 up into the thousands. Contributors’ pledges are only used when the project has reached its funding goal, thus reassuring investors that their money is constructively going to a go-project. These various price tiers are very important (especially for musicians) because the amount a fan contributes is directly related to their level of commitment to the artist, and the goods or services being offered in return.

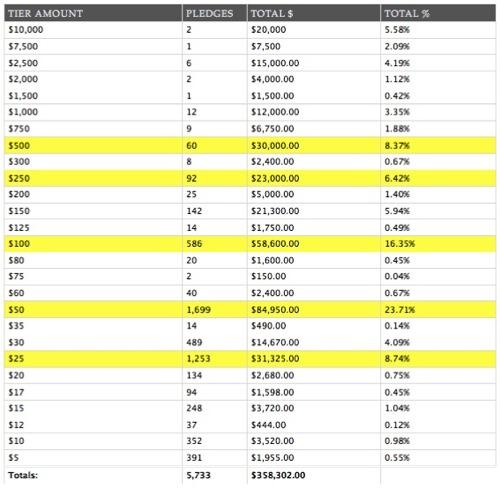

In selecting price tiers for the funding of their book, Mod and Rawlings looked at the top 30 grossing Kickstarter campaigns to determine which tiers would be the most effective. This provided Craig with data that he could use –in his words– to “look for a balance between number of pledges and overall percentage contribution of funds.” The following graph illustrates his findings:

In a blog post from his Official Website, craigmod.com, Mod shares his insights on the

“This data is, of course, hardly perfect (for example, not every project I looked at used the same tiers). But it’s good enough to give us a sense of what price ranges people are comfortable with. The $50 tier dominates, bringing in almost 25% of all earning. Surprisingly, $100 is a not too distant second at 16%. $25 brings in a healthy chunk too, but the overwhelming conclusion from this data is that people don’t mind paying $50 or more for a project they love. It’s also worth contemplating going well beyond $100 into the $250 and $500 tiers: they scored relatively high pledging rates compared to other expensive tiers. The lower tiers — less than $25 — are so statistically insignificant (barely bringing in a combined 5% of all pledges) that I recommend avoiding them. Of course this depends on your project — perhaps there’s a very good reason for a $5 tier. More importantly, this data shows that people like paying $25. Having too many tiers is very likely to put off supporters. I’ve seen projects with dozens of tiers. Please don’t do this. People want to give you money. Don’t place them in a paradox of choice scenario! Keep it simple. I’d say that anything more than five realistic tiers is too many.”

In the case of musicians, Mod’s findings seem to correspond well with the multi-tiered product offerings that are gaining popularity on most artists’ websites. $1 downloads, $25 CD/ Poster sets, all the way up to the $250 box sets; these price tiers cater to the varying level of a fan’s commitment to an artist. It is worth noting that, for musicians, the $25 tier might be a bit more useful than Mod and Rawlings found it to be in their book campaign. Nonetheless, Mod’s data illustrates the fact that lower price tiers are far less effective (accounting for only 5% of total earnings). In addition, giving investors too many options to contribute small sums of money, in a way, encourages them to give less instead of more –which to a degree, defeats the overall purpose of the campaign. By limiting a contributor’s options to a handful of specifically defined ranges with corresponding rewards attached, supporters are forced to think bigger in terms of their donations.

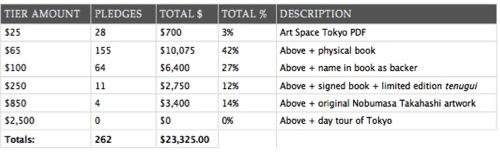

Based on the data collected, Mod and Rawlings put together the following price tiers with corresponding rewards for each:

Illustrating the point made above, the table shows that the lowest price tier offered ($25) only generated 3% of the total earnings. A paltry 28 people (11% of total contributors) opted for this tier while 155 (59%) went for the $65 tier. Also, the $100 tier got more than double the donations than the $25 tier (64 compared with 28). Lastly, as the amount of each tier climbed, the number of contributions proportionally dwindled, yet the $850 tier still pulled in a higher percentage of total earnings than the $250 tier with only 4 supporters.

Promotional Considerations

To spread word of the campaign, Mod and Rawlings engaged in an online promotional plan that focused on their permission-based social medial touch points, as well as key design blogs and magazine sites that were completely in target with their psychographics and demographics. They focused their messaging campaign using Twitter and Facebook (their messaging was relevant and minimal, too), as well as their own mailing list. Mod and Rawlings had built up an extensive mailing list of design and art world contacts over the past 6 years, which they leveraged nicely.

See, below, an example of the artwork used for the email, and another spreadsheet with the timing and results of their targeted email campaigns:

Perhaps the most impressive part of the whole campaign was Mod’s outreach strategy to the blogs that he felt were in line with what he was doing with his project, and his method of communication to them. He was not focused on the quantity of external outreach; rather, he was more interested in the quality of the blogs he gave focus to. This is a marketing strategy that creators of all kinds would do well to consider. As Mod describes it:

“I’m writing to blogs that I’ve been reading for years, so for me, referencing older posts of theirs and personalizing these emails is trivial, and fun. Whatever you do, don’t send scattershot emails to media outlets. Be thoughtful. The goal is to appeal to editors and public voices of communities that may have an interest in your work, not spam every big-name blog. A single post from the right blog is 1000% more useful than ten posts from high-traffic but off-topic blogs. You want engaged users, not just eyeballs!”

Points To Keep In Mind

Rawlings and Mod’s book may be only a starting point to think about fan funding strategies for musicians. But there is a lot to learn from them. First of all, Rawlings and Mod had a clearly defined plan. While they did not have anywhere near the clout that a Trent Reznor-type would have, they knew exactly how much money they needed and who they were going to target to generate the funds. They were also very strategic in how they approached their campaign. They knew their demographic, and they knew what sort of incentives would be appealing at the various price points that they presented. If musicians approached fan funding with this level of organization and preparation, the result could be just as effective.

By Michael King

Edited by Evan Kramer