A Force Not A Face

Redefining the Role of Women in the Music Business in the Aftermath of #MeToo, Ke$ha and Taylor Swift

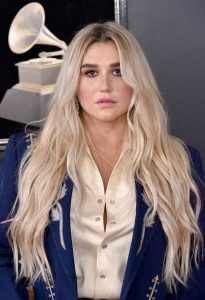

All eyes were on Ke$ha at the 2018 Grammy Awards. Joined on stage by a slew of pop music’s female A-listers donned in all-white—the preferred uniform of 20th century suffragettes, Ke$ha delivered an emotional rendition of her piano-centric ballad, “Praying”. Her performance, the first single she released in over four years, was touted as an anthem for strength, support and empowerment, marking the closing scene in her lengthy and turmoulous legal battle with producer, Dr. Luke. The highly-publicized saga of lawsuits, accusations, counter-suits, amendments, injunction requests and subsequent denials, ultimately resulted in the dismissal of all claims against Dr. Luke, a name now more infamously associated with years of alleged sexual, physical, verbal and mental abuse over an impressive discography.

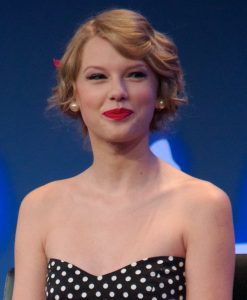

A few months after Ke$ha’s final counterclaim was overturned, another lengthy sexual misconduct trial surrounding a high-profile female artist began resurfacing in the headlines. Dubbed a “symbolic lawsuit” due to the $1 in damages sought, Taylor Swift was determined to make an example out of David Mueller, the radio DJ she claimed groped her at a 2013 meet-and-greet. Shortly following the incident, Muller was fired and sued Swift, claiming false allegations and subsequent defamation. Swift shot back with a countersuit for assault and battery, assuming the role of a self-appointed crusader for “other women who may resist publicly reliving similar outrageous and humiliating acts.” When a jury unanimously agreed that Mueller had inappropriately touched Swift, it marked a win for women, validation for Swift and a preview of the impending storm on the verge of shaking Hollywood with an influx of sexual misconduct allegations against high-profile actors, media personalities and executives. The movement, coined #MeToo, spiraled into an international conversation and quickly became synonymous with sexual harassment and assault awareness in the workplace.

Ke$ha’s “Praying” performance at the Grammy Awards, as well as Taylor Swift’s timely inclusion as a “silence breaker” on the cover of Time Magazine’s Person of the Year issue, symbolize both women’s personal empowerment and experiences, but are also a nod to the greater #MeToo movement. Still, though media outlets were eager to designate “Praying” as the Grammy’s “Me Too moment”, the music industry had remained relatively quiet in the revolution ravaging through the neighboring TV and movie world. As dozens of allegations began to unravel in the height of the #MeToo, music industry executives notably only comprised a small percentage of those accused. Simultaneously, accusations made by actresses far outnumbered those by female musical artists. Experts cite a number of factors to explain the omission, but it was certainly not the result of immunity or innocence to misconduct.

The music industry has historically been regarded as, and arguably still is, a “boy’s club”, both culturally and statistically. Despite the inescapable empires of female icons like Rihanna, Adele and Beyonce, 83.2% of artists in 2017 were men while only 16.8% were women—a six year low. Behind the scenes, the gap widens: in a study conducted by the Annenberg Inclusion Initiative at USC analyzing the top 600 performing songs from 2012 to 2017, only 12.3% of the 2,767 credited songwriters were female and women accounted for only 2% of all producers. Given these numbers, it is not surprising that women also receive less opportunities and recognition compared to their male counterparts; 73.8% of female songwriters only worked once in 6 years and of the 899 individuals nominated for a Grammy Award between 2013 and 2018, 90.7% were men. Of the 20 executives serving on the board of the Recording Industry Association of America, only four are women. Additionally, the Power 100, Billboard’s annual list of leaders in live, tech, management and recorded music, included 17% women in 2018, up from the previous year’s 10%. Overall, “the voices of women are missing from popular music”, concludes Dr. Stacy Smith, a professor at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism and lead researcher behind the Annenberg Inclusion Initiative.

In a 2016 report, the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission Task Force outlined several risk factors associated with heightened workplace harassment including lack of diversity, significant power disparities and and workplace cultures that encourage alcohol consumption. The blatant minority status of women coupled with the industry’s casual “sex, drugs and rock ’n’ roll” attitude, forges new challenges for the women that make up 28% of the sound recording industry’s workforce, in addition to the business’s already competitive nature. The anonymous accounts of several women, silenced by non-disclosure agreements and fear over losing their jobs, consistently identify risk factors and create a similar picture: an environment where “deals are sealed over late-night drinks and at backstage parties” and the role of “one of the guys” is often assumed in order to flourish. For many of these women, accepting, tolerating, and downplaying harassment is the acceptable response to ensure job security. Because women are often working closely alongside men with control over their careers, a situation some men take advantage of, ignoring these advances or discontinuing to work with them may not be an option. One woman feared earning a reputation as “sexual harassment girl” at the record label where she worked. “I thought people wouldn’t want to hire me because they wouldn’t understand, and think I’m being over-sensitive to something that was just normal in the music industry”, she elaborated. In another accounts, women come to terms with the inappropriate behavior as a necessary evil; “It is a male dominated industry…I do remember the days where I was collaborating with a group of guys who would say really gross jokes….I was just going to let it happen because I wanted to play my songs.” An industry built and thriving on this model, despite blatant sexism and complete desensitization to harassment, does not have much of an incentive to systematically change. Of course, underrepresentation and discrimination of women in business is not exclusive to the music industry. However, within an industry that has thrived by exploiting musicians for over a century accompanied by an often all-consuming lifestyle of business and pleasure, the risk of misconduct is heightened. According to Ginger Clark, a psychology professor at USC’s Rossier School of Education who specializes in women’s issues and trauma, “it creates the perfect environment for this sort of thing to take place”.

Unsurprisingly, the hostility and barriers facing professional women in the music business inevitably induces a shortage of females leaders, mentors and role models in the industry, continuing the cycle of female underrepresentation and a boys’ club mentality. Melissa Woods, Head of Creative Services and A&R at Los Angeles and Montreal-based Third Side Music recommends offering girls an opportunity to explore fields such as music composition or engineering at a young age. She, like countless others, credits her own success to working alongside many strong females in music, confidently concluding that “the more women there are to mentor and support one another, the better off the industry will be”. Recently, a great deal of focus has been put on female-to-female mentorship to bridge gaps for women in the entertainment industry. Voices in Entertainment, a grassroots anti-harassment effort founded by a pair of female music executives, recommends three tangible steps for amending a wide range of the industry’s gender and equality issues: mentorship, getting more women in executive positions and educating the current group of young women working in the music industry “so they can understand their worth, what their paths can be and having more women represented across the board”.

Regardless of the music business’s role, or perhaps lack of, in the #MeToo movement, an unspoken culture still casts a shadow across women in entertainment, regardless of age, stage or popularity—both in front of and behind the scenes. I am hopeful that the conversation and awareness stemming from the aftermath of Taylor Swift’s sexual assault trial, Ke$ha’s legal battle with Dr. Luke and #MeToo begins to uproot the convenient dismissal of harassment and misconduct as “just the way things are” or “part of the business”— in Hollywood, on Broadway and in small concert venues across the country. Still, celebrating these instances as progress is generous; Muller, the radio DJ found guilty of groping Taylor Swift, just started a new job at a radio station in Mississippi and Ke$ha’s final attempt to exit her contract with Dr. Luke was dismissed under the premise that his “allegedly abusive behavior was foreseeable”. Despite these outcomes, the conversation has been started, problems have been identified and solutions have been prescribed. Perhaps the music industry is approaching the eve of its own #MeToo-inspired movement. Perhaps scandal will be dodged completely and changes will rapidly and anxiously ensue to avoid a Weinstein-esque degradation of the music industry. Regardless, women in music deserve to be recognized as a force and not just a face; “women in music deserve more than a forgettable #MeToo moment at the Grammys”. I am optimistic that the conversation will evolve beyond sexual misconduct and eventually address other crucial, yet less urgent, roadblocks hindering women in music—underrepresentation, pay gaps, lack of opportunities and a shortage of female role models. The ultimate goal? “Eradicating inequality in entertainment.”

Works Cited

Domanick, Andrea. “The Dollars and Desperation Silencing #MeToo in Music.” Noisey, March 15, 2018.

United States. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Select Task Force on the Study of Harassment in the Workplace. By Chai R. Feldblum and Victoria A. Lipnic. 2016.

Finkelstein, Sabrina. “A Timeline of Events Leading Up to Taylor Swift Groping Trial.” Billboard, August 7, 2017.

Goldstein, Jessica. “Judge Rejects Kesha’s Latest Effort to Void Contract, Suggests Dr. Luke’s Abuse Was ‘foreseeable’.” ThinkProgress. March 22, 2017.

Johnston, Maura. “Women in Music Deserve More than a Forgettable #MeToo Moment at the Grammys.” NBC News, January 28, 2018.

Marcus, Bonnie. “The Music Industry Remains A Boy’s Club: How Do Women Break In?” Forbes, April 3, 2018.

McDermott, Maeve. “Why #MeToo Hasn’t Taken off in the Music Industry.” USA Today, January 22, 2018.

Pajer, Nicole. “New Report Shows Major Lack of Representation by Women in the Music Industry.” Billboard, January 25, 2018.

Sisario, Ben. “Gender Diversity in the Music Industry? The Numbers Are Grim.” New York Times, January 25, 2018.

Smith, Stacy L. “Inclusion in the Recording Studio?” Annenberg Inclusion Initiative, January 25, 2018.

Vincent, Alice. “Kesha’s Comeback: A Timeline of Her Bitter Legal Feud with Sony and Producer Dr Luke.” The Telegraph, January 29, 2018.

Zaleski, Annie. “New Initiative Hopes to Bring #MeToo to the Music Industry.” Rolling Stone, February 1, 2018.